Black Worker Advocates Launch the #WorkingWhileBlack Campaign

Houston Style Magazine, February 27, 2017.

National Black Worker Center Project to Trump and Members of Congress: “Bring a permanent end to the economic abuses of Black workers with a vision that goes beyond the desire for political power.”

Washington, DC— The National Black Worker Center Project, a national network dedicated to addressing the multi-dimensional Black work experience, announced its launch today of the #WorkingWhileBlack campaign to expose the impacts of racial and economic injustice in the workplace.

The launch comes one day before President Donald Trump’s first address to a joint session of Congress where he is expected to outline budgetary and economic goals. It also follows the public release of a letter to then President-elect Trump from the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) urging him to seek the its council regarding the “New Deal for Black America” and its impact on millions of African Americans in the areas of job creation, finance and trade reforms, and new infrastructure investments.

“We often hear about Black workers’ high unemployment rates and over-representation in low-wage jobs in the ‘inner-cities’,” said Tanya Wallace-Gobern, Executive Director of the National Black Worker Center Project (NBWCP). “The Black work experience, however, includes a wide spectrum of policy supported injustices suffocating our families and our communities across the economic strata, regardless of geography, profession, skills sets, or income level.”

WorkingWhileBlack will specifically raise public awareness about the unique structural threats and obstacles, in Black communities, of low-wages, unemployment and underemployment, job discrimination, labor organizing and the concrete ceiling facing Black professionals. As part of the effort, NBWCP leaders will amplify the voices of Black workers by creating public forums and calling on the Trump administration, federal and state level policymakers to effectively address job issues that silence the achievements of Black workers and prevent advancement.

“Forms of economic racism and exploitation rise when politicians have narrow vision,” said Wallace-Gobern. “Consequently, exploitation, institutional racism, and job abuses are maintained by political and corporate structures that preserve power and wealth for select few. #WorkingWhileBlack says bring a permanent end the economic abuses of Black workers with a vision that goes beyond the desire for political power.”

Official NBWCP Response to President Trump and the DOJ

From the start of his candidacy, and throughout his presidency, Donald Trump has waged a war of words on Women, Black and Brown people. That war continued this weekend with his incredibly disturbing and racist tweets, The NBWCP strongly condemns his hateful, divisive, racially charged rhetoric, and we are committed to continuing our fight against oppression and inequity. Now more than ever, we are reminded of the necessity and significance of our civic engagement, especially during the upcoming election season.

Trump’s Dog whistle politics are direct attacks on people of color. We call on those who believe that diversity is an American strength to stand in solidarity with our brothers and sisters who have been directly and indirectly impacted by the President’s words, and the social and political climate that has been created as a consequence of those words.

Regretfully, an additional deeply troubling announcement came this week, with yesterday’s announcement that the NYPD Officer who choked unarmed Black man Eric Garner to death would not face federal charges. The NBWCP is shocked, saddened, and angered to know that yet another black life has been deemed as dispensable by the criminal justice system. We are rallying with, and around, every individual raising their voices in protest around the country to speak truth to power, and cry out against these injustices.

Despite the President and other public officials making statements and decisions that seem regressive to the strides that we have made in civil rights, we would like to affirm to all marginalized groups- including the Black workers who toiled thankless for centuries to build this country- that you are valued, and your voices and lives matter.

We will continue to fight for the powerless, and with you, until we usher in an era where there is truly liberty and justice for all.

In Solidarity,

The National Black Worker Center Project

People First Raleigh Mayoral and City Council Candidate Forum

On October 2nd we partnered with the NC APRI Piedmont Chapter, Black Workers for Justice, National Domestic Workers Alliance, Raise Up for 15, and PowerUp NCLCV to host the ‘People First’ Candidates Forum that focuses on issues impacting Black & Brown communities in Raleigh.

Co-op-Style Black Worker Centers Tackling Unemployment

Yes Magazine (by Melissa Hellman).

(10/04/16) — Delonte Wilkins was looking for a fresh start when he was released from Pennsylvania’s Schuylkill Federal Correctional Institution in February. He polished his resume and applied to several jobs in his hometown of Washington, D.C. But when he was turned down for three job offers once those employers learned of his criminal background, Wilkins soon realized he couldn’t easily leave his felony behind.

“I already know that I’m not going to pass the background check.”

“I’m discouraged from applying to a lot of different jobs because I already know that I’m not going to pass the background check,” says Wilkins, a certified electric systems technician. He doubted there was a space for African American workers with histories like his to thrive, particularly in Washington, D.C., where the Black unemployment rate is the highest in the country, according to a 2015 Economic Policy Council report. Seven months ago, while seeking information about black worker-owned cooperatives, he joined a labor center to learn about workers’ rights and civic engagement.

The D.C. Black Workers Center, established two years ago, is where Wilkins found employment possibilities, and a place that helps to build economic empowerment for African Americans in the city. Located in the United Black Fund building, which houses Black nonprofits, the D.C. Center takes a unique approach to its job-training services by addressing the twofold crises of high unemployment among Black workers and the low wages they’re paid when they do find work. It is one of eight African American worker centers nationwide. The other centers are located in Los Angeles, Chicago, Oakland, Calif., Greenville, Miss., Boston, and Raleigh-Rocky Mount, N.C. A center in Baltimore is opening soon.

“You build the most power when people are actively participating in shaping their own lives.”

The National Black Workers Center Project, a national network that supports all of the centers, is working to shift the narrative on African American unemployment, which is 8.1 percent, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics—nearly double that of Whites. Steven Pitts, a board member at The Project, says that Black workers need to organize because they lack the power to influence public policy and attain economic freedom. He says it’s the fundamental reason for high unemployment and low-wage positions, what he calls the Black job crisis.

“A closely related concern is the public narrative about [its] causes and solutions,” says Pitts, who’s also a labor economist at U.C. Berkeley. This is why one of the Project’s first initiatives, Working While Black, will feature multimedia stories on their website about African American workers and local campaigns to improve access to high-quality jobs. The storytelling initiative will launch in mid-November.

The National Black Workers Center Project drew inspiration from immigrant centers that cropped up in the 1990s to offer legal services and advocacy for the influx of Latin American and Asian immigrants. In a similar fashion, the Black Workers centers use a member-led structure to address the unique challenges facing African American workers—namely racial prejudice, discriminatory hiring practices, and the disproportionately high incarceration rate. “You build the most power when people are actively participating in shaping their own lives,” says Pitts.

To do this, the organizers conduct surveys and hold listening sessions to adapt to the needs of the area. After noticing that Black construction workers were not being hired to work on new rail lines, the LA Center hosted a campaign to successfully employ more African Americans in the county’s transportation projects. In Oakland, the Bay Area Black Workers Center was part of a coalition that convinced the county’s board of supervisors to vote in favor of hiring 1,400 formerly incarcerated residents for various positions with the county in June. A coordinating committee in Baltimore is also in the beginning stages of creating a labor center to address the predominantly African American city’s vast income inequality.

Cooperatives allow communities to determine where they work and how much they’ll be paid.

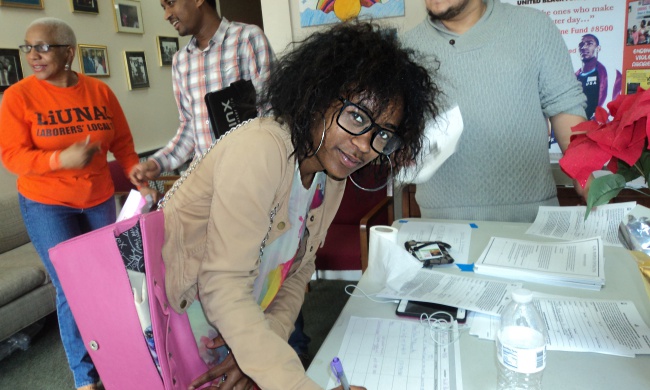

In D.C., the Center focuses on reducing the unemployment gap. In addition to job training, organizers partner with labor unions and offer construction skills trainingto increase access to higher-wage positions. Some desired jobs include railroad maintenance work, demolition and asbestos removal, and construction on federal government projects, which pay up to $30 an hour. So far, 25 members have received general construction skills training, and 10 of them were offered jobs with construction companies.

They also teach members cooperative organizing. Last year, members received training in workplace democracies, in which they learned how to recruit other workers and create their own cooperatives. Lawyers explained the legal steps of developing a cooperative, and some members shared their observations from a visit to a child care cooperative in West Philadelphia. The visit has inspired some women at the D.C. Center to start a child care co-op.

Wilkins says the Center emphasizes co-ops because they have a democratic approach that allows all of the workers to have equal footing. To him, cooperatives allow communities to determine where they work and how much they’ll be paid. Housing, food, and jobs are “a human right,” he says, “not a commodity.”

Delonte Wilkins, left, with another organizer, facilitates monthly meetings with Southeast residents. Photo courtesy of Dominic Moulden.

Unlike other job training hubs in the city, the D.C. Center provides a space for members, at their monthly meetings, to have cathartic conversations about their work experiences. Sometimes they discuss the discrimination they face for having African American names, or talk about deconstructing Black respectability politics, in which African Americans police their own values to fit into the White mainstream. Overall, the meetings focus on topics ranging from the fight for a $15-minimum wage to organizing labor unions. Up to 40 people regularly attend the meetings, although there are about 1,200 in the Center’s database.

The D.C. Center fills the gap between training and employment opportunities.

Members sit around a large table wearing work attire ranging from suits and ties to auto-mechanic jumpsuits. During some sessions, labor unions conduct workshops on organizing low-wage retail workers, and familiarize workers with their rights. “The purpose of the Black Worker Center is to create a space where people build power and understand the politics of their work, where they build skills to enhance their opportunity to get good work, and where, through co-ops organizing, we can control and create our own labor,” says Dominic Moulden, a resource organizer at the D.C. Center.

Moulden recruits members by walking door to door, and talking to strangers, in laundromats and metro stops. During these engagement walks, he estimates he and other members have asked nearly 100 people about their employment history and career goals. Members then brainstorm ways to offer resources related to the community’s concerns.

During recruitment sessions, Moulden, who has worked in D.C. as an organizer for various social justice campaigns for the past 30 years, discovered that some workers with low-wage jobs had received multiple certificates and ample training, but they were still unable to get ahead. “People were trained to death, but still unemployed,” he says. So, they partnered with the construction worker union LiUNA, the Laborers’ International Union of North America, to provide members with training on construction and asbestos removal. In March, the labor union held an intake session for D.C. Center members and connected them with companies that offered 10 jobs.

Raymin Diaz, a union labor and community organizer at LiUNA Mid-Atlantic, says the D.C. Center fills the gap between training and employment opportunities. Many of the area’s other training facilities do not offer a clear pathway to a job, he says. Although the capital is teeming with construction sites, Diaz says he often encountered overqualified workers with skills certificates who were unable to find employment.

“They all have the same goal: more access for housing, more clothing, more food, more shelter.”

“Unfortunately the individuals who live in that city and pay tax money are not profiting from that boom. A lot of them are being pushed out of the city,” Diaz says. LiUNA seeks to change that by offering Black Workers Center members construction skills training, collecting job applications, and connecting them with union contractors. LiUNA’s partnership with the Center works toward the common goal of ending systemic disenfranchisement, he adds. Diaz says he hopes members will find one sustainable job instead of relying on several gigs to support their families. “Collectively, our effort is to give everyone a fair shot.”

At the beginning of next year, the D.C. Center will roll out its apprenticeship pilot program, ApprenticeShift, which trains Black workers to code. As part of their fundraising, they’ve asked the city’s workforce investment council to divest nearly $3 million from failed work development programs and reallocate the funding to the tech initiative. Wilkins says the program will go forward without it, but they’re not sure how long it will last if they don’t have that support.

It’s not just people from the Black labor movement who favor the centers. Cultural workers, like vegan chef Elijah Joy, joined the D.C. Center as an advisory council member to network with others and to learn about worker cooperatives. He dreams of one day starting a food co-op that embraces local produce, Black culture, and personal history. Food deserts are common where the Center is located in Southeast D.C.

“What I see in D.C. is that there’s a lot of need, but there’s also a lot of people doing great work,” Joy says, but he found that similar organizations rarely shared ideas. “They all have the same goal: more access for housing, more clothing, more food, more shelter.” He plans on using the organizing skills he has learned at the Center to collaborate with organizations aimed at improving African American residents’ health and wellness.

It’s been only two years, and the D.C. Black Workers Center has offered job skills training and moral support to hundreds of African American men and women, and has even helped some of them find jobs and start co-ops. And although it focuses on helping workers find employment at outside establishments, some members have been hired as staff. After being rejected for several jobs in his field because of his criminal record, Wilkins was recently hired by the D.C. Center as an organizer. What’s paramount in the fight for economic empowerment, Wilkins says, is that everyone at the Center has a voice, and works together to address the needs of the community.

“Building economic power in D.C. is necessary to gain the liberation that I want,” he says.

Millions in U.S. Climb Out of Poverty, at Long Last

NY Times (By Patricia Cohen) — http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/26/business/economy/millions-in-us-climb-out-of-poverty-at-long-last.html?smid=fb-share&_r=1

(9/26/16) — Not that long ago, Alex Caicedo was stuck working a series of odd jobs and watching his 1984 Chevy Nova cough its last breaths. He could make $21 an hour at the Johnny Rockets food stand at FedEx Field when the Washington Redskins were playing, but the work was spotty.

Today, Mr. Caicedo is an assistant manager at a pizzeria in Gaithersburg, Md., with an annual salary of $40,000 and health benefits. And he is getting ready to move his wife and children out of his mother-in-law’s house and into their own place. Doubling up has been a lifesaver, Mr. Caicedo said, “but nobody just wants to move in with their in-laws.”

The Caicedos are among the 3.5 million Americans who were able to raise their chins above the poverty line last year, according to census data released this month. More than seven years after the recession ended, employers are finally being compelled to reach deeper into the pools of untapped labor, creating more jobs, especially among retailers, restaurants and hotels, and paying higher wages to attract workers and meet newminimum wage requirements.

“It all came together at the same time,” said Diane Swonk, an independent business economist in Chicago. “Lots of employment and wages gains, particularly in the lowest-paying end of the jobs spectrum, combined with minimum-wage increases that started to hit some very large population areas.”

Poverty declined among every group. But African-Americans and Hispanics— who account for more than 45 percent of those below the poverty line of $24,300 for a family of four in most states — experienced the largest improvement.

Government programs — like Social Security, the earned-income tax credit and food stamps — have kept tens of millions from sinking into poverty year after year. But a main driver behind the impressive 1.2 percentage point decline in the poverty rate, the largest annual drop since 1999, was that the economy finally hit a tipping point after years of steady, if lukewarm, improvement.

Over all, 2.9 million more jobs were created from 2014 to 2015, helping millions of unemployed people cross over into the ranks of regular wage earners. Many part-time workers increased the number of hours on the job. Wages, adjusted for inflation, climbed.

“Another hidden benefit was lower prices at the pump,” Ms. Swonk said. “People who couldn’t afford the commute before could now afford to accept a minimum-wage job.”

There are different roads out of poverty, said Sheldon Danziger, president of the Russell Sage Foundation, a social science research institution, but today, one of the most promising is to “go somewhere where they raised the minimum wage.”

About 43 million Americans, more than 14 million of them children, are still officially classified as poor, and countless others up and down the income ladder remain worried about their families’ financial security. But the Census Bureau’s report found that 2015 was the first year since 2008, when the economic downturn began, that the poverty rate fell significantly and incomes for most American households rose.

“If you look under the hood of the census report,” Michael Strain, director of economic policy studies at the conservative research organization American Enterprise Institute, said, “you see more people are working, so fewer people are going to be in poverty.”

After a long period of rising inequality, Elise Gould, an economist at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute in Washington, added, the benefits of the improving economy finally began to seep downward. Wage increases were “even stronger at the bottom than in the middle,” she said.

For those on the lower rungs of the income ladder, a step upward can be profound. For some, it means the difference between sleeping on a friend’s couch and having a home. For others, it is the change from getting shoes at Goodwill to buying a new pair at Target, or between not having the money to buy your daughter an ice cream cone to getting her a bicycle for her birthday.

The poverty rate fell in 23 states, with Vermont leading the way. The rest stayed flat; none got worse. And other evidence suggests the improvement has continued, if not as strongly, this year.

Mr. Caicedo, 32, initially found his job on Craigslist last summer, starting at $12 an hour. Recently, he was promoted to his salaried position and now drives a 2015 Nissan Pathfinder. His wife was able to leave her job at a clothing store and take care of their four children.

Michael Lastoria, who started the chain called & Pizza where Mr. Caicedo works, said: “We try to pay as close to a fair or living wage as possible,” roughly $2 an hour above the minimum with a steady full-time schedule and benefits. “We want people to have careers, not just jobs,” he said.

The availability of full-time jobs at a livable wage may be essential to move out of poverty but is not necessarily enough. Many poor people, saddled with a deficient education, inadequate health care and few marketable skills, find small setbacks can quickly set off a downward spiral. The lack of resources can prevent them from even reaching the starting gate: no computer to search job sites, no way to compensate for the bad impression a missing tooth can leave.

Many of those who made it had outsize determination, but also benefited from a government or nonprofit program that provided training, financial counseling, job hunting skills, safe havens and other services.

Cheyvonné Grayson, 29, grew up in South-Central Los Angeles, where he, at the age of 14, saw a friend gunned down. Since graduating from high school, Mr. Grayson has worked mostly as a day laborer. In 2014, he was paying $300 a month to sleep on someone’s couch and showing up at 6 a.m., morning after morning, at nonunion construction sites in the hopes of getting work.

Often the supervisors and workers spoke only Spanish, and it was hard to understand the orders and measurements. He remembered one foreman looking him up and down, skeptical that he could do the job.

“I had to prove this man wrong,” Mr. Grayson said.

At every site, he said he tried to pick up skills, carefully observing other workers, asking questions and later reinforcing the lessons by watching YouTube videos. Even so, the work was inconsistent and paid poorly, he said.

What made the difference, he said, was getting into the carpenters’ union — a feat he could not have achieved without the help of the Los Angeles Black Worker Center. “That was the door opener,” Mr. Grayson said.

He had to borrow a few hundred dollars for fees and tools, but his first apprenticeship as a carpenter started at $16.16 an hour. He quickly moved up to $20.20 an hour and is paid for his further training. He is now hanging doors for new dormitories at the University of Southern California.

For the first time in his life, he opened a bank account.

Seventeen hundred miles east, Christine Magee, a mother of four, joined an intensive self-sufficiency program administered by the Chicago Housing Authority and the Heartland Alliance after she fell into bankruptcy from racking up $22,000 in debt on a credit card. As a recipient of a federal housing voucher, Ms. Magee was eligible to enroll.

She set three goals after joining the program in 2014: buy a house, raise her dismal credit rating and get a better job that would provide for her retirement someday.

“She was really motivated,” said her counselor, Barbara Martinez. “Not everyone is.”

Ms. Magee’s husband has found only sporadic work. But she has moved from a health-technician job that paid $23,000 a year and left her family on Medicaid to one at a veterans hospital that pays more than $35,000 and provides health and educational benefits. The extra earnings automatically went into an escrow account.

A couple of weeks ago, she graduated from the program with more than $8,000 in savings — which she plans to use for a down payment on a home — and a bank letter confirming she qualifies for a mortgage.

“I knew,” Ms. Magee said, “there was something more out there.”

#WorkingWhileBlack and the Weekly News Wrap Up

View Original Article (reprint of Worker’s Independent News coverage; includes audio link).

The Union Edge, March 10, 2017