Baltimore Brew (By Will Kirsch)

Organizers of a new workers’ resource in Baltimore invoke the history of past labor struggles.

Coming together in a West Baltimore classroom on the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance, a group of people reflected on one aspect of the civil rights icon’s work – his history of fighting for exploited, underemployed and underpaid black workers.

In a city whose African-American residents still endure structural inequality, poverty and joblessness, the group launching a Baltimore Black Worker Center yesterday saw themselves as essentially addressing the same issues half a century later.

“Militarism, exploitation and racism” were three evils that Dr. King saw as posing the greatest threat to black people, said Lenora Knowles, a doctoral student at the University of Maryland College Park and member of local feminist organization Black Womyn Rising.

King’s Poor People’s Campaign and his support of the Memphis sanitation workers may have taken place decades ago, but they have a literal resonance and relevance for black workers today, Knowles said.

Gathering at Coppin State University, the recently formed committee comprised of lawyers, students, workers and activists held their inaugural meeting using labor’s most reliable weapon – organization.

Knowles said the center will serve as a place where black workers and their allies can plan and coordinate their fight against economic injustice.

“The center is about building black worker power here in Baltimore, in the workplace and in our community as a whole,” said Knowles, emphasizing the intersectional nature of the group’s work.

“We kind of see ourselves as this hub of synergy between unions and community groups and we’re trying to have a space which moves in ways other organizations have not and can not,” she added.

The said the center will organize unionized and non-unionized workers as well as social justice and advocacy groups to address the many forms of oppression in contemporary Baltimore.

Girding for Battle

The Baltimore center is affiliated with the National Black Workers Center Project, whose aim is “to address the crisis of unemployment and low-wage work.”

Its organizers say they want to do more than provide traditional job training: “We also must find strategies that combine strategic research, service delivery, policy advocacy, and organizing to improve the quality of jobs that are available in the economy.”

The project has spawned similar centers in Washington and Los Angeles that offer education, research and advocacy, as well as employment networking.

In Baltimore, the town hall style kick-off event attracted a number of different speakers and several dozen participants.

Committee member Courtney Jenkins, representing the American Postal Workers Union and the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, reflected on how the center could work with unions.

“I’m hoping that what it can give to unions is perspective on the state of working conditions in the real world,” said the 29-year-old.

He also observed that the center might be a place for workers to learn how to organize and to teach about workers’ legal rights.

The town hall began with a brief history of black labor in Baltimore led by Coppin State University professor Ken Morgan.

“When we’re talking about civil rights movements, we’re talking about today,” Morgan said, connecting past and present struggles. That theme of a battle yet to be won defined the tone of the meeting.

The committee presented part of their report, “The State of Black Workers in Baltimore,” that discusses racially stratified inequality that defines American labor.

They also put forth a loose structure of their future plans for action, listing outreach, research and education as three broad goals.

Committee members also discussed the group’s recent survey, which reached out to black workers in the Baltimore area to hear about their experiences in the workplace.

They found that the most often cited barrier to getting ahead in the workforce was racial discrimination, regardless of industry.

Feeling Under-valued

Some audience members echoed the organizers’ theme of learning from past battles.

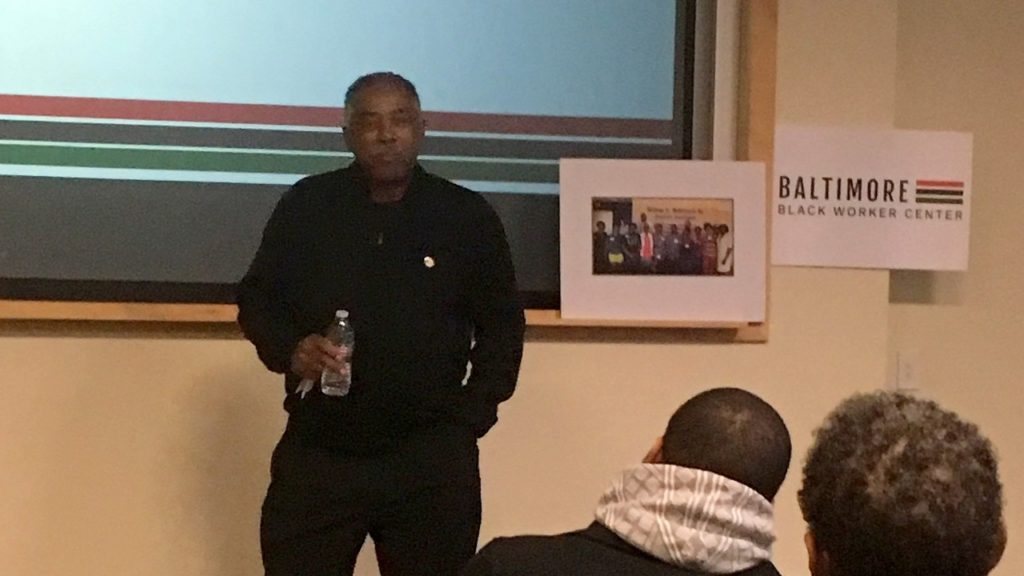

“Revolutionary work is conscious work,” said Fred Mason, president of the Maryland-D.C. chapter of the AFL-CIO, urging listeners to bone up on the history of black labor in America.

Workers, both union and non-union, shared their experiences as black people in the city work force.

Alberta Palmer and Robin Gaines, an organizer and a member of the service union Unite Here!, spoke about their current negotiations with Johns Hopkins University over benefits for food service employees.

Another worker, not represented by a union, told the audience that he felt underpaid, under-valued and over-worked at his maintenance job in a nearby apartment building.

The final speaker was a young man named Antwon Jordan, whose shirt was emblazoned with the “No Education, No Life” slogan of the Baltimore Algebra Project.

Jordan offered a different perspective, saying that he hoped the center would be a place for young black people to develop their talents.

Fred Mason, MD-DC AFL-CIO chapter president, at the launch of the Black Worker Center in Baltimore. (Will Kirsch)