Budget Proposal Plus Washington Politics Equals A Bad Deal For Black Workers

Huffington Post, March 17, 2017.

The fate of Black workers will not lie in the hands of Washington policymakers.

In recent days, headlines are screaming optimism in regards to the nation’s economy. Corporate leaders and the White House administration, say the economy is getting stronger. The Bureau of Labor reported a gain of 235,000 jobs in February—with major gains in construction, manufacturing, healthcare— and a 4.7 percent unemployment rate.

Meanwhile, Washington politicians and President Trump are proposing $54 billion in federal budget cuts that will lead to massive federal worker layoffs. The f

ederal reserve is increasing interest rates in the face of a 2% inflation rate that will push up costs for mortgages, car loans and credit cards. And, the recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reported that 24 million people would lose health care coverage over the next 10 years if the proposed House Republican Obamacare repeal is enacted.

Those industries that added jobs? That’s where Black workers are overrepresented in low-wage positions and disconnected from training and apprenticeships.

For millions of Black workers and our families, the economic outlook isn’t so bright and the gains, proposed policies and cuts are hardly optimistic.

For millions of Black workers and our families, the economic outlook isn’t so bright and the gains, proposed policies and cuts are hardly optimistic. In fact, they would likely lengthen the bridge to economic justice and maintain poverty structures that halt full engagement of Black workers in the U.S. economy, particularly for Black women who still face wide wage gaps and are less likely to work in higher-paid occupations.

Even in a good economy, the Black unemployment rate (currently 8.4 percent) consistently remains twice as high as the national average. Nationally, the unemployment rate for Black women is 7.1 percent.

Let’s take a closer look. In Chicago, the jobless rate for Black 16- to 19-year-olds, in 2014, was 88 percent, per a report released by the University of Illinois-Chicago’s Great Cities. A new Los Angeles Black Worker Center report (pending release) cites that the median wage of Black women is only 67% of what white men earn and about 81% of what white women earn. In Baltimore, Black labor economist Steven Pitts found that while Blacks comprise 27.6% of the total workforce and 36.2% of the low-wage workforce, Black female workers make up 40.8% low-wage workers. There, the industries with the highest numbers of low-wage Black workers are restaurants, grocery stores, hotel accommodations, retail, and arts and entertainment.

The Black jobs crisis goes beyond unemployment and underemployment. It extends to racist hiring practices wage and salary discrimination, unjust corporate practices, and concrete ceiling that prevent advancement opportunities. Elected officials snub the necessary, deeper discussions about these policies and practices already ill-serving the nation’s Black workers. They favor political theater instead and whole communities suffer.

As part of the #WorkingWhileBlack campaign, the National Black Worker Center Project (NBWCP) and its affiliates are actively seeking ways to address the Black jobs crisis that locks Black workers out of the nation’s economic prosperity, especially women.

In 2013, Los Angeles Black Worker Center (LABWC), led by Black women, successfully negotiated an employment agreement with the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority (MTA,). Their agreement mandated that 40 percent of the work hours go to “disadvantaged workers.” Later this month, LABWC will release two reports: “Ready to Work, Uprooting Inequity,” as well as “Black Spaces for Women” – a report for a pilot project with curriculum recommendations― for affiliates of the National Black Workers Center Project to help improve practices that support Black womens’ leadership

The Baltimore Black Worker Center, in celebration of Women’s History Month, is hosting a forum, “From Girls in the Hood to Women in Construction,” to provide space for Black workers to get connected to apprenticeship programs and building trades. It’s the first in a series of forums to educate workers about what they need for apprenticeships with non-traditional trades.

Optimism for Black workers in a growing economy should rest in our own organizing efforts to strengthen political power, change policies and end systemic racism that blocks access to equal wages and job advancements.

The fate of Black workers will not lie in the hands of Washington policymakers. Find out more about the National Black Worker Center Project and join the #WorkingWhileBlack campaign to help ensure that Black workers at all levels reap the same benefits of economic growth as the rest of the nation.

#WorkingWhileBlack – Exposing Impacts Of Racial And Economic Injustice

Workers Independent News (WIN Radio), March 10, 2017.

The National Black Worker Center Project is launching a #Working While Black campaign advocating a “New Deal for Black America”.

Executive Director Tanya Wallace-Goburn says to Trump and members of Congress that they should bring an end to the economic abuses of Black workers with a vision that goes beyond the desire for political power.

[Tanya Wallace-Goburn]: “Rather than focusing on filling the pockets of and wallets of billionaires, we need to focus on building projects that don’t extract wealth from our communities and build wealth within our communities.

And that’s something that all of us – no matter what your race or ethnicity is – can align with.”

The #Working While Black campaign will expose the impacts of racial and economic injustice in the workplace through workers telling their stories.

[Tanya Wallace-Goburn] :”And our goal is to launch a strategic communications and organizing campaign that’s designed to mobilize and communicate the experiences and challenges, aspirations and achievements of Black workers.

Black work has been synonymous with low paying jobs that leave Black workers vulnerable.”

The Congressional Black Caucus is urging Trump to seek its council on “The New Deal For Black America” And Wallace-Goburn says the national Black Worker Center Project partners with organized labor.

[Tanya Wallace-Goburn]: “We consider ourselves fortunate to partner with organized labor.

The main ways that we see participation is in our membership. There are many African-Americans that are members of unions and they are also members and supporters of the National Black Worker Center Project.

The other way that we’ve been able to partner with labor is in understanding the necessity to having better jobs created.”

Movement for Black Lives Pushes for Victories City by City

Next City, February 27, 2017.

Six months ago, social and economic justice groups with a stake in what’s largely known as the Black Lives Matter movement illuminated an exit path out of decades of systemic racism in the U.S.

Beneath the banner of the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), and arguing the disparities faced by black communities across the U.S. had to be broken down “not [by] reform but transformation” of a swath of contemporary laws, they proposed policies that took a page out of progressive theories on urban development that would reverberate across the spectrum of race and class at the city level. Tax incentives for local businesses that make their workforce more diverse. Shifting more federal funds out of police departments and into employment programs. Favoring community-based sustainable energy projects that employ neighbors.

Half a year in, organizers say, they’re still working out a way forward — and dealing with the November 2016 election of President Donald Trump.

“There were very few people who were not blindsided,” says Cathy Albisa, executive director of the National Economic and Social Rights Initiative (NESRI). Her organization is one of those that helped to craft the M4BL platform.

Their approach thus far has been to act local but think national, by influencing policymakers in the cities where M4BL’s main players operate: New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Washington, D.C., Sacramento, Portland, Ferguson and a handful of others. They’re unified by that city-scaled approach, but when asked about the organization’s national front, Albisa says she’s “not sure what anyone’s strategy is three weeks into the new administration.”

The uncertainty is understandable. Trump’s speeches thus far suggest his gaze on urban issues will lead us leaps away from the legacy laid out by former President Barack Obama. His appointment to run the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Ben Carson, has expressed inconsistent opinions about federal assistance programs for low-income and underserved communities.

Last week, members of both the House and the Senate served up two bills pleading for a permanent version of the New Markets Tax Credit program, which has helped create 750,000 jobs through $75 billion in investments in cities across the country, but it’s still too early to say how this administration will fare on urbanism.

For now, Thenjiwe McHarris, co-founder of movement builder Blackbird, says M4BL groups are turning anxiety into energy at the ground level while the federal government takes form.

“We recognize that, considering the violent political climate and the current administration, our focus must be on supporting visionary local reform,” she says. That means providing educational resources for small groups that want to bring the M4BL policies to their own cities, and creating spaces in cities and online where “organizations can dream, scheme and implement needed reforms.”

Those reforms, she says, will “mitigate the immediate threats against our people while allowing us to build the power and vision we need to actualize the [M4BL] platform.”

Part of that means linking up with national movements that were gathering momentum since before Trump took office. Through the M4BL, Albisa and NESRI have started collaborating with the Black Youth Project 100, an advocacy group focused on millennials that’s currently putting its weight behind the $15 minimum wage campaign in Chicago. Forty-six percent of black workers in that city work low-wage jobs.

Last fall, the National Black Worker Center Project (NBWCP) joined other workers’ rights groups at a meeting with the U.S. Department of Labor to push one of the biggest economic reforms on the M4BL list: They demanded an update to a 1965 anti-discrimination law, to ensure an increase in the percentage of black workers hired for federal projects, noting: “It is unconscionable that it has not been updated in 36 years, given the increased diversity of our nation’s population and the growing poverty in our communities.”

Since August, M4BL organizers say they’ve influenced a few successful divestment campaigns at the city level. Last week Alameda, California, removed millions of dollars of its shares in Wells Fargo because of that bank’s active role in financing private prisons and the Dakota Access Pipeline. At the end of January, racial and economic justice group Enlace, an affiliate of the Movement for Black Lives, helped a student group organize and push the University of California school system to divest $475 million from Wells Fargo for the same reason.

No matter their next effort, Albisa says, the vitriol of the presidential campaign only reinforced how necessary a guiding light the M4BL policies can be across the next four years. “That work of pushing forward at a moment like this is more valuable than we even realize,” she says.

The Equity Factor is made possible with the support of the Surdna Foundation.

#WorkingWhileBlack and the Weekly News Wrap Up

View Original Article (reprint of Worker’s Independent News coverage; includes audio link).

The Union Edge, March 10, 2017

ISO More Jobs, Better jobs, Black Worker Center launches

Baltimore Brew (By Will Kirsch)

Organizers of a new workers’ resource in Baltimore invoke the history of past labor struggles.

Coming together in a West Baltimore classroom on the annual Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance, a group of people reflected on one aspect of the civil rights icon’s work – his history of fighting for exploited, underemployed and underpaid black workers.

In a city whose African-American residents still endure structural inequality, poverty and joblessness, the group launching a Baltimore Black Worker Center yesterday saw themselves as essentially addressing the same issues half a century later.

“Militarism, exploitation and racism” were three evils that Dr. King saw as posing the greatest threat to black people, said Lenora Knowles, a doctoral student at the University of Maryland College Park and member of local feminist organization Black Womyn Rising.

King’s Poor People’s Campaign and his support of the Memphis sanitation workers may have taken place decades ago, but they have a literal resonance and relevance for black workers today, Knowles said.

Gathering at Coppin State University, the recently formed committee comprised of lawyers, students, workers and activists held their inaugural meeting using labor’s most reliable weapon – organization.

Knowles said the center will serve as a place where black workers and their allies can plan and coordinate their fight against economic injustice.

“The center is about building black worker power here in Baltimore, in the workplace and in our community as a whole,” said Knowles, emphasizing the intersectional nature of the group’s work.

“We kind of see ourselves as this hub of synergy between unions and community groups and we’re trying to have a space which moves in ways other organizations have not and can not,” she added.

The said the center will organize unionized and non-unionized workers as well as social justice and advocacy groups to address the many forms of oppression in contemporary Baltimore.

Girding for Battle

The Baltimore center is affiliated with the National Black Workers Center Project, whose aim is “to address the crisis of unemployment and low-wage work.”

Its organizers say they want to do more than provide traditional job training: “We also must find strategies that combine strategic research, service delivery, policy advocacy, and organizing to improve the quality of jobs that are available in the economy.”

The project has spawned similar centers in Washington and Los Angeles that offer education, research and advocacy, as well as employment networking.

In Baltimore, the town hall style kick-off event attracted a number of different speakers and several dozen participants.

Committee member Courtney Jenkins, representing the American Postal Workers Union and the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, reflected on how the center could work with unions.

“I’m hoping that what it can give to unions is perspective on the state of working conditions in the real world,” said the 29-year-old.

He also observed that the center might be a place for workers to learn how to organize and to teach about workers’ legal rights.

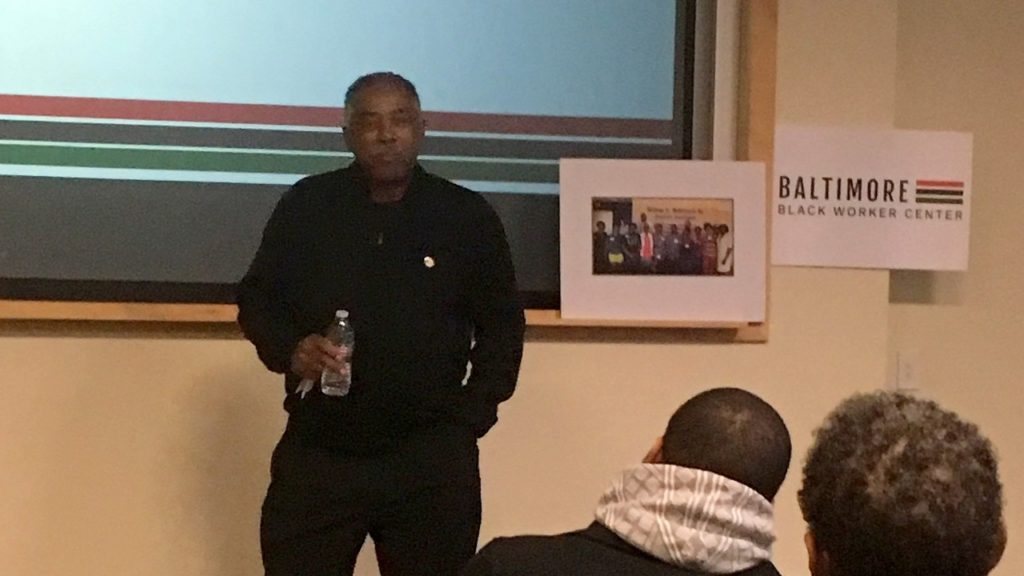

The town hall began with a brief history of black labor in Baltimore led by Coppin State University professor Ken Morgan.

“When we’re talking about civil rights movements, we’re talking about today,” Morgan said, connecting past and present struggles. That theme of a battle yet to be won defined the tone of the meeting.

The committee presented part of their report, “The State of Black Workers in Baltimore,” that discusses racially stratified inequality that defines American labor.

They also put forth a loose structure of their future plans for action, listing outreach, research and education as three broad goals.

Committee members also discussed the group’s recent survey, which reached out to black workers in the Baltimore area to hear about their experiences in the workplace.

They found that the most often cited barrier to getting ahead in the workforce was racial discrimination, regardless of industry.

Feeling Under-valued

Some audience members echoed the organizers’ theme of learning from past battles.

“Revolutionary work is conscious work,” said Fred Mason, president of the Maryland-D.C. chapter of the AFL-CIO, urging listeners to bone up on the history of black labor in America.

Workers, both union and non-union, shared their experiences as black people in the city work force.

Alberta Palmer and Robin Gaines, an organizer and a member of the service union Unite Here!, spoke about their current negotiations with Johns Hopkins University over benefits for food service employees.

Another worker, not represented by a union, told the audience that he felt underpaid, under-valued and over-worked at his maintenance job in a nearby apartment building.

The final speaker was a young man named Antwon Jordan, whose shirt was emblazoned with the “No Education, No Life” slogan of the Baltimore Algebra Project.

Jordan offered a different perspective, saying that he hoped the center would be a place for young black people to develop their talents.

Fred Mason, MD-DC AFL-CIO chapter president, at the launch of the Black Worker Center in Baltimore. (Will Kirsch)